Paraphrase

Paraphrasing is the reformulation of a message in a different way without altering its meaning (Translated from Larousse, 2016). It is an excellent strategy for processing and understanding abstract information in assignments, exams or in a text from which a summary, analysis or commentary is to be written (Barbeau et al., 1997).

To develop a paraphrase, it is essential to understand the meaning of the text and to rewrite it in your own words, not forgetting to indicate the source of the text you have paraphrased. Sometimes paraphrasing is more than just rewriting a paragraph, an idea or a text. Sometimes it may require a more elaborate explanation to demonstrate an understanding of the concepts. It is an explanatory development that requires a thorough understanding of an extract from a text, of a concept. A paraphrase is therefore not a summary, it is an explanation of the text, sometimes longer, sometimes shorter than the original text.

As an example, we can paraphrase this paragraph:

"The reasons for this difficult journey through the school system are complex. One of them is rarely addressed in studies on the subject, although it deserves special attention: the difficulties that mastery of the language of schooling can represent for Indigenous students" (Hot, 2013 p. 63).

Paraphrase 1 :

One aspect of Indigenous education research that has not been much addressed is the question of why Indigenous students have difficulty mastering the language of schooling.

Paraphrase 2 :

The reasons for difficulties in the language of schooling for Indigenous students are little addressed in research on education.

Advantages

Developing a paraphrase allows you to quickly identify what is not understood. If you cannot rephrase an idea, it means that you do not fully understand its meaning.

To get started

When a teacher gives you a text to read, which is the subject of an assignment or assessment:

- Paraphrase certain passages that you find difficult or important;

- Show this paraphrase to your teacher, who will confirm or not your understanding of a directive, question, text, etc.

Questions to ask yourself :

- How would I explain the excerpt or statement in my own words?

- How would I explain the excerpt to someone else, if I had to?

Exercise

UQAM, s.d.

- Read several times the text you have to paraphrase in order to have a good understanding of it;

- From memory, rewrite the excerpt in your own words, i.e. as if you were spontaneously explaining it to someone;

- Substitute the important words, such as nouns, adjectives, verbs, adverbs, relationship markers). Stay true to the meaning of the writer's words;

- Change the sentence structure to personalise it to your writing style;

- You can also practice playing with words by changing the order and using a synonym dictionary. However, using these methods alone does not necessarily produce a good paraphrase.

To integrate this strategy

- Choose a text to read (or that you have read) in a course;

- Paraphrase a part that you find important or difficult;

- - Apply this procedure to another text you have to read in another course, adapting your approach;

- Apply this same process to all the reading you need to do for your courses. To avoid discouragement:

- do this exercise twice immediately (with two different texts);

- repeat this exercise tomorrow, two more times, trying to do it better and a little faster;

- Repeat this exercise once a day for the next three weeks, trying to get it right and speeding up your pace when possible. Apply this strategy to all your academic reading.

Summarise

Summarising means rephrasing an author's ideas in your own words for better understanding. The text can be a book, a chapter, an article, etc. In this way, readers become aware of the structure of a text and how ideas are linked together. Summarising focuses on the main ideas and allows generalising and minimising the less relevant details (Trabasso and Bouchard, 2003).

The summary is also an abridged or condensed version, presented either at the end of a volume, an article, an oral communication, an event or a phenomenon. The purpose of a summary is to recapitulate and sometimes to conclude (Legendre, 2005). The summary is also a basis for personal and professional documentation. It can be useful to a superior or a subordinate to facilitate the understanding of a given file, hence the importance of developing the ability to write a summary clearly, concisely and precisely (Morfaux and Prévost, 2009). The summary will also be very useful for your reading cards.

The summary does not include any evaluation or personal reflection; it provides the reader with the essential elements of the document without, however, emphasising any particular aspect. The role of a summary is essentially informative.

Advantages

Allows you to gain a better understanding of the texts you read and better retention of the information.

To get started

When reading a text, it is important to always summarise in a few words the ideas in the text . Summarise in 10 words the content of a paragraph, a page, two pages.

The criteria for a good summary

Morfaux and Prévost, 2009

- Be clear : an effective summary is one that is presented in an orderly fashion with secondary ideas well connected to the main ideas. Examples can be given only if they are essential to the understanding of an abstract concept. It is not always necessary to write an introduction and a conclusion. You should stick to what is required by your teacher.

- Be faithful : avoiding distortions of an author's words that you are trying to summarise. The objective and indirect form (the use of the third person) gives the author responsibility for his statements. It is not forbidden to use the author's words as they are, but they should be placed in quotes " ".

- Be brief: the length of a summary may vary from teacher to teacher. Usually, a summary should be limited to the essentials and it is important to strictly comply with teachers' expectations.

What a summary must include

- The full reference of the document;

- Information about the author if relevant;

- The main elements of the problem, the author's intentions and/or assumptions;

- The theme and main idea;

- Sub-themes and secondary ideas;

- A description of the text as a whole;

- Striking elements (optional).

Exercise

- Scan the document;

- Do a first reading of the document, in a global way, in order to get an overview of it. You can start to identify the important passages;

- A second reading will allow you to identify the key words or important words that help to express the main ideas. Identifying the tool words (or linking or transition words) is also important to see how the text is organised;

- Analyse the text, paragraph after paragraph, paying special attention to transitions;

- Take notes: for each paragraph, or for a set of paragraphs, write a paraphrase to summarise the ideas;

- Select the relevant information to be included in the summary (do not include details that are unnecessary for understanding, even if they are interesting for you);

- Develop the writing plan;

- Present the ideas in the same order as the author. Reuse the paraphrases you wrote in the previous steps;

- Include transition words for a logical flow of ideas;

- Write the draft;

- Make the corrections and proper presentation.

Example of a summary

Short :

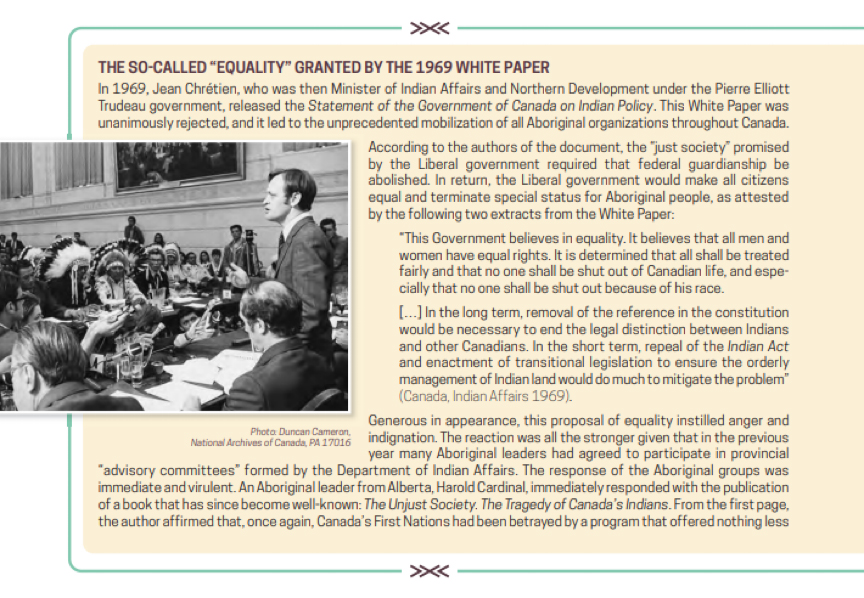

In his book Aboriginal Peoples: Fact and Fiction, in Chapter 4, entitled Dealing with Different Rights, anthropologist Pierre Lepage provides a summary of the context surrounding the publication of the 1969 White Paper, The Indian Policy of the Government of Canada, in Chapter 4, entitled Dealing with Different Rights. With this policy, the government aimed to restore a more just society by abolishing Indian status. However, by offering no recognition in return to Canada's Indigenous people, they unanimously rejected the Government's proposals. This indigenous mobilisation led, among other things, to the creation of the Assembly of First Nations (formerly the National Indian Brotherhood of Canada), and in 1982, to the recognition and protection of the fundamental rights of Canada's Indigenous peoples.

Long :

In 1969, Jean Chretien, who was then Minister of Indian Affairs and Northern Development, released the Statement of the Government of Canada on Indian Policy. This White Paper was unanimously rejected, and it led to the unprecedented mobilization of all Aboriginal organizations throughout Canada. The White Paper proposed a just society to end federal trusteeship. Aboriginal organisations united and mobilised to reject the proposals in the paper, which would undermine the special status of the country's Aboriginal people. A response to the government is made in the writings of an Aboriginal man from Manitoba, Mr. Harold Cardinal, who once again describes the government's proposals as "cultural genocide" since, according to him, "the only good Indian in Canada is a non-Indian" (Cardinal, 1969: 1). In 1970, the Alberta Indian Chiefs published Citizen Plus, a Red Book, which suggested that Indians should be recognised as "advantaged citizens" since they had additional rights to other Canadians. This recommendation was made by the Hawthorn and Tremblay Commission in 1966. This book reminds the Government of its obligations under the treaties it has signed. The government's policy was eventually abandoned, and as a result, indigenous organisations sprang up across Canada. The National Indian Brotherhood was created in 1970, which later became the Assembly of First Nations in 1980. These organisations succeeded in having their voices heard because in 1982, when the Canadian constitution was repatriated, the fundamental rights of indigenous peoples were protected.

Sources :

Lepage, P. (2019). Aboriginal Peoples: Fact and Fiction, 3rd edition. Commission des droits de la personne et des droits de la jeunesse and Institut Tshakapesh.P. 44.

Write a synthesis

Synthesis includes the summary, but goes far beyond it because of its more complex nature (Morfaux and Prévost, 2009). Synthesis often involves the comparison and confrontation of texts from different sources, which requires a total reorganisation of the order of ideas, without altering the meaning of the texts.

Synthesis involves analysis just as in the preparation of a summary; however, synthesis involves the analysis of several texts. This analysis is not about extracting the main ideas from each of the texts. The synthesis task is selective, which means that it must retain from each text the ideas that are relevant to the ideas in the other texts. Thus, the essential ideas of a text in itself will be set aside, since it is only on the point of comparison that the articulation of the synthesised text must be built.

Advantages

Allows you to take a critical distance from the texts you read and to compare them.

To get started

- Global reading of the texts: this first reading allows students to become familiar with the texts, and to identify words and transition words in order to understand the structure of the text.

- Analytical reading: in this second reading, through a systematic analysis of each text, identify the main and secondary ideas related to it. Note the articulations and representative examples. At the end of this stage, you will have the ideas and their connections. You can then compare these ideas with each other.

- The synthesis plan: make a plan after having looked for existing relationships from one text to another, which link or oppose the ideas.

- Pitfalls to avoid:

- A synthesis is not a simple juxtaposition of text summaries;

- Be careful not to eliminate all examples and thus become too abstract;

- Avoid mechanically comparing similarities and differences between the texts; instead, see how ideas complement or contradict each other, for example;

- Avoid highlighting unrelated details at the expense of key ideas;

- Avoid jumping from one idea to another and back to one of them later.

- What you must do:

- Look for a perspective that can be coordinated, i.e. a way of bringing a certain fluidity to the text, between the points of view, from which it will be possible to build a logical synthesis plan;

- Use a short sentence announcing the subject addressed as an introduction and as a thread;

- Group the authors' positions in relation to each other and to the subject of the synthesis. Clearly mark (by different paragraphs, for example) the moments of progression in your text, i.e. when you move on to the next idea.

Exemple [1] :

Between Decolonization and Indigenization: How to Think About a Fairer World? (Annual CIÉRA conference 2022, Free Translation)

[…]However, we could define indigenization more broadly. This concept can be understood as the opening of spaces and institutions to Indigenous thoughts. This requires the inclusion of Indigenous people in the decision-making bodies of these spaces and institutions and the inclusion of their knowledge and their way of doing things in the decisions made by these spaces and these institutions (Melançon 2019). Indigenization involves a process of change within institutions that allows for the establishment of physical and epistemic spaces that take into account Indigenous perspectives (Pete 2016).

More specifically, Adam Gaudry and Danielle Lorenz (2018), drawing on the Canadian academic context, conceive Indigenization from a three-part spectrum. On one end is Indigenous inclusion, in the middle reconciliation indigenization, and on the other end decolonial indigenization. For these authors, Indigenous inclusion corresponds to the implementation of policies aimed at increasing the number of indigenous people within institutions. This dimension of indigenization does not challenge colonial structures. Rather, it requires Indigenous people to adapt to them. The creation of an indigenous contingent integrated into state police forces is an example of this type of indigenization (Aubert and Jaccoud 2009). Reconciliation indigenization aims to put non-Indigenous knowledge and practices on an equal footing with those of Indigenous people in order to achieve a new balanced relationship. This dimension of indigenization requires the development of collaborative mechanisms, an effective transformation of decision-making processes and the inclusion of First Peoples in the decision-making environments that affect their lives. Reconciliation involves changing institutions to include Indigenous perspectives. Finally, decolonial indigenization describes practices that aim to fundamentally reorient the functioning of institutions. This dimension relies heavily on resurgence thinking to reimagine institutions. In academia, this means rethinking the way knowledge is produced to make more room for Indigenous knowledge. Decolonial indigenization therefore aims to transform institutions into something dynamic and new that promotes a climate of social justice within them. The definitions proposed by Gaudry and Lorenz is relevant, because it makes it possible to distinguish different degrees of indigenization according to the policies put forward by the institutions. It can also be used for different contexts, including the museum environment (Franco 2020), the primary and secondary education environment (Paul, Jubinville and Lévesque 2020; Donald 2009) and the health environment (Lavallee and Poole 2009) . In light of the under-representation of Indigenous peoples and their knowledge in these institutions, Indigenous practices are more necessary than ever.

In these perspectives, we wish to question the link between indigenization and decolonization in theory and in practice. For several authors who have a very important influence in Indigenous decolonial studies, this link does not exist (Alfred 1999, Simpson 2017, Coulthard 2014). Grouped under the title of “traditionalists”, these thinkers imagine a decolonization that can only take place outside colonial institutions, which therefore comes into profound contradiction with all definitions of indigenization. For them, the values between Indigenous and non-Indigenous societies are so immeasurable that it is impossible to think of the end of colonial relations (therefore decolonization) in a relationship with non-Indigenous societies.But for other authors, this perspective is philosophically and practically untenable. It is impossible to conceive of an Indigenous identity that reflects an image of unchanged culture, untransformed by colonialism (Rifkin 2012). Nor is it possible to think of a colonial identity unaffected by the actions of Indigenous peoples (Schotten 2018, 58-9). Even if relations are unequal and it is obvious that colonial actions affect Indigenous people, this relationship must still be taken into account to imagine one day, equality between these different societies. Although these authors consider that there are indeed differences between Indigenous and non-Indigenous values (since without these differences there would be no material for thinking about Indigenous self-determination and decolonization), these differences are not insurmountable. […]

For full text and bibliography, consult the following page (in French, free translation) : CIÉRA. (2022). Entre décolonisation et autochtonisation : Comment penser un monde plus juste? Colloque annuel du CIÉRA 2022.

https://www.ciera.ulaval.ca/colloque-annuel-du-ci-ra/accueil

Sources :

1 CIÉRA. (2022). Entre décolonisation et autochtonisation : Comment penser un monde plus juste? Colloque annuel du CIÉRA 2022. https://www.ciera.ulaval.ca/colloque-annuel-du-ci-ra/accueil

Writing a critical review

The critical review is a summary which includes an evaluative or critical component. It may also include a particular extension of a theory under study or offer insights into specific aspects of a summarised publication.

The critical part can either be presented separately from the summary (in which case it is presented at the end of the document) or be integrated into the summary. In this case, you should clearly distinguish the paragraphs or sentences related to the criticism, so as not to create confusion. In either case, your introduction should mention the summary as well as the criticism.

The number of pages in a review may vary according to the expectations of the teachers. The critical part can vary between 10 and 50% of the text. The critique of a text consists of an evaluation of the text and the reasons for its evaluation, in other words, an examination of the author's ideas and approach. A critique cannot cover all the elements of the text. You will need to focus on one or more relevant elements: the main or secondary ideas, the flow of the text as a whole, the innovations of the work in the field of knowledge, the limits of the research or the content addressed, etc. This assessment should be well-founded and qualified, based on sound arguments and a fair understanding of the text. You should also bear in mind that your criticism is itself open to criticism.

Advantages

A critical review helps you develop your evaluation capacity by taking a critical distance from what you read.

To get started

Steps

- Read the document as a whole, then read it actively;

- Summarise the text as described in the summary section;

- The full reference should appear at the beginning of the document;

- For each of the aspects evaluated or critiqued, note the contributions and limitations of the text, giving counter-arguments for each.

Example 1 :

Excerpt from a research report (Crépeau, 2012), which is a critical review of research on reading strategies in post-secondary education.

Research on reading strategies in relation to post-secondary education provides some answers to our research question. First, Martinez and Amgar's study of students (1997) enrolled in university programs who failed the Quebec Ministry of Education and Higher Education's French writing test attempts to describe good readers and those who consider themselves as facing difficulties. It was found that readers who consider themselves in difficulty use few semantic strategies, activate their prior knowledge less and are less satisfied with themselves as readers. The main limitation of this study is that the quantitative instruments used are relevant for large groups, but do not provide in-depth knowledge of the students' reading experience. Other researchers have developed ways to assess students' awareness of their reading strategies (El-Koumy, 2004; Miholic, 1994; Mokhtari and Reichard, 2002; Mokhatri and Sheorey 2002; Mokhtari, Sheorey and Reichard, 2008; Schmitt 2005; Shoerey and Mokhtari, 2001). These studies show that students with low levels of awareness and control of their reading strategies often have difficulty coping with academic reading tasks (Mokhtari andd Sheorey, 2002; Mokhtari, Sheorey and Reichard, 2008). Another study, which examined students' perceived use of reading strategies and the difference between effective and less effective readers on a reading proficiency test, showed that students in the proficient group used a wider variety of reading strategies than less proficient readers (Razak and Amir, 2010). To sum it up, the instruments used in this research, based on self-assessment, raise certain criticisms, including the lack of precision of certain statements (in relation to the context), thus causing diverse interpretations by the students. Therefore, these measurement tools must be used in conjunction with other more objective tools. Finally, the results must also be interpreted with care since awareness of strategies does not mean that the student uses them (Mokhtari and Reichard, 2002; Mokhtari and Shoerey, 2002; Mokhtari, Sheorey and Reichard, 2008; Sheorey and Szoke Baboczky, 2008).

Example 2 :

Excerpt from a critical review written by Julie-Anne Bérubé for the SOA3001 course at UQAT, on a text by Van Ingen and Halas (2006)2.

In the intercultural schools studied, the authors' conclusion from their observations is that students have difficulty taking their place in a school system that does not recognise their cultural or intellectual identity, and does not expect them to succeed. The authors then provide a statistical portrait of Indigenous schooling in Manitoba, which is among the lowest in the country. In the section where the authors discuss absenteeism, they talk about a significant number of students who are frequently absent from their courses (Van Ingen and Halas, 2006). The text lacks, as it does here, a reference to the number of students observed to come to this conclusion, or the percentage of students observed exhibiting these behaviours, etc. The authors rarely indicate the number of respondents, and do not qualify their statements in relation to the small (or large) number of students in whom these behaviours were observed. The authors use terms such as "a number of", "significant numbers of" and "some" to make strong statements and quantify the analyses when these terms, in my opinion, should lead to more qualified assumptions. This leads me to believe that the authors may be inclined to generalise from observations obtained from only a small number of individuals.

Exercise :

To develop critical reviewing skills, choose a book in your field of study. At the end of each chapter, summarise its contents in half a page. Then write a half-page review.

Sources :

1 Refers to the reader's use of meaning and context to understand what is being read (Martinez and Amgar, 1997)..

2 Van Ingen, C et Halas, J. (2006). Claiming Space : Aboriginal Students within School Landscapes. Children’s Geographies, 4 (3), 379-398.